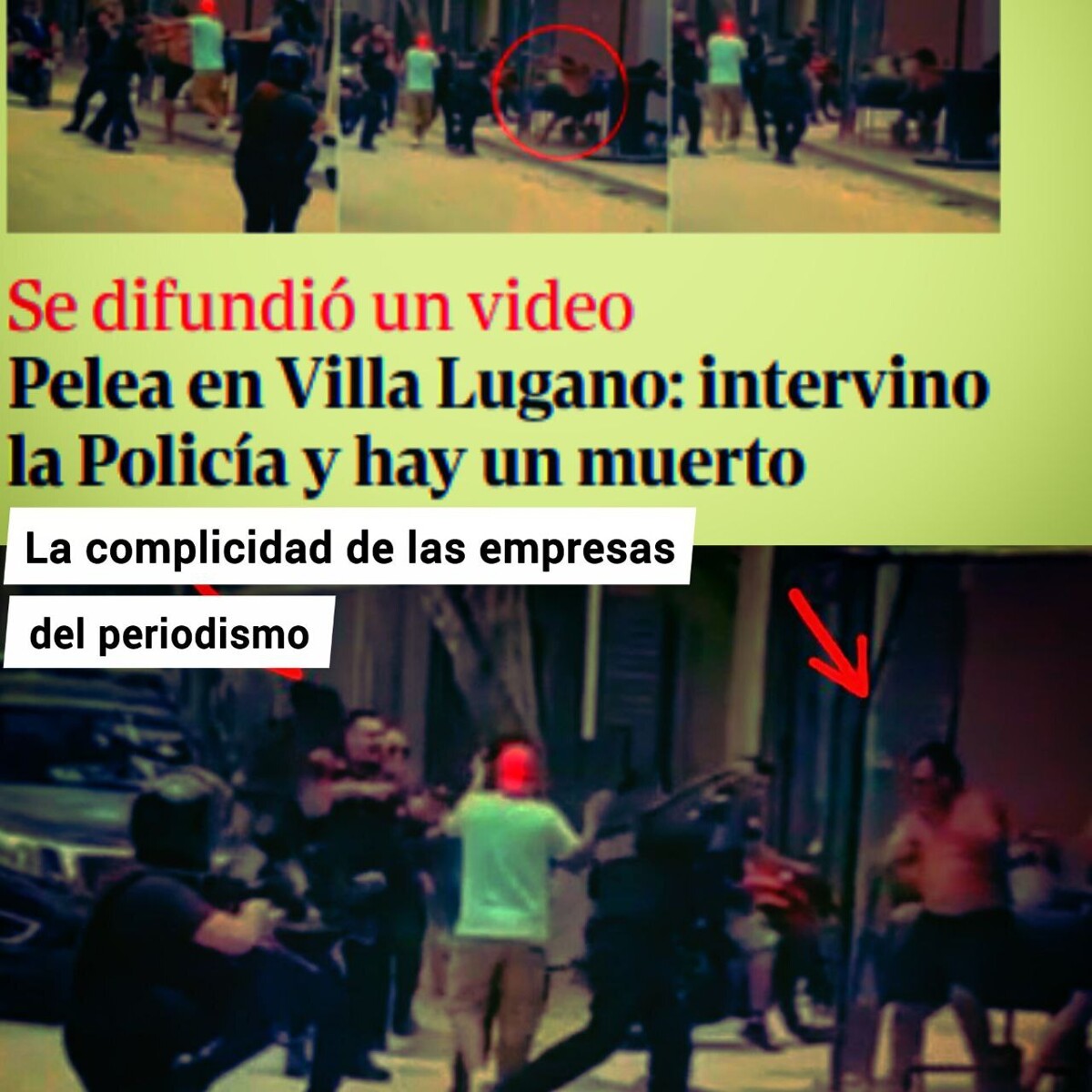

For this reason, once again, both in 2002 and now, we report and insist: the police caused a new death, not the crisis. In the face of the evident crime committed at Christmas by officers of the City Police in Villa 20 in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Villa Lugano, Clarín once again betrays journalism and hides responsibility with the headline 'Fight in Villa Lugano: Police intervened and there is one dead.' As when it headlined in June 2002 that 'The crisis caused two new deaths,' referring to the murders of Darío Santillán and Maximiliano Kosteki during the Avellaneda Massacre. That headline became emblematic because it condenses a way of narrating events that dilutes political and material responsibilities. There were no police who fired, no state that repressed, no government decisions: it was 'the crisis,' an abstraction without subjects or culprits, that appeared as the author of the deaths. Language thus operated as a tool for covering up. That headline was not an isolated error, but the expression of an editorial line that sought to depoliticize state violence and protect those responsible in power. That is why, once again, both in 2002 and now, we report and insist: the police caused a new death, not the crisis. To counter this way of communicating, contribute financially, spread the content, or join us in building community, alternative, popular, and self-managed media. More information related: Alternative media were decisive in learning the truth of the Avellaneda Massacre. 'Someone gave the order, they were looking for dead people and to stop the social conflict.' As when it headlined in June 2002 that 'The crisis caused two new deaths,' referring to the murders of Darío Santillán and Maximiliano Kosteki during the Avellaneda Massacre. In the face of the evident crime committed at Christmas by officers of the City Police in Villa 20 in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Villa Lugano, Clarín once again betrays journalism and hides responsibility with the headline 'Fight in Villa Lugano: Police intervened and there is one dead.' 'There was a brawl with neighbors and one of them died,' is the subheading of Clarín's note, in a clear revival of 'they killed each other.' 'There was a brawl with neighbors and one of them died,' is the subheading of Clarín's note, in a clear revival of 'they killed each other.' 'Officers of the force went to the area after a call about disturbances.' 'Officers of the force went to the area after a call about disturbances.' By presenting the facts as an inevitable consequence of a quasi-natural crisis, Clarín contributed to building a narrative that equated victims and victimizers, and that deactivated the possibility of a structural reading of the economic model and the political decisions that led to broad sectors of the population marginalized by the economy to organize and take to the streets. More than twenty years later, with the advance of the right in the region and much of the world, Clarín and most of the hegemonic media maintain the same logic when it comes to reporting.